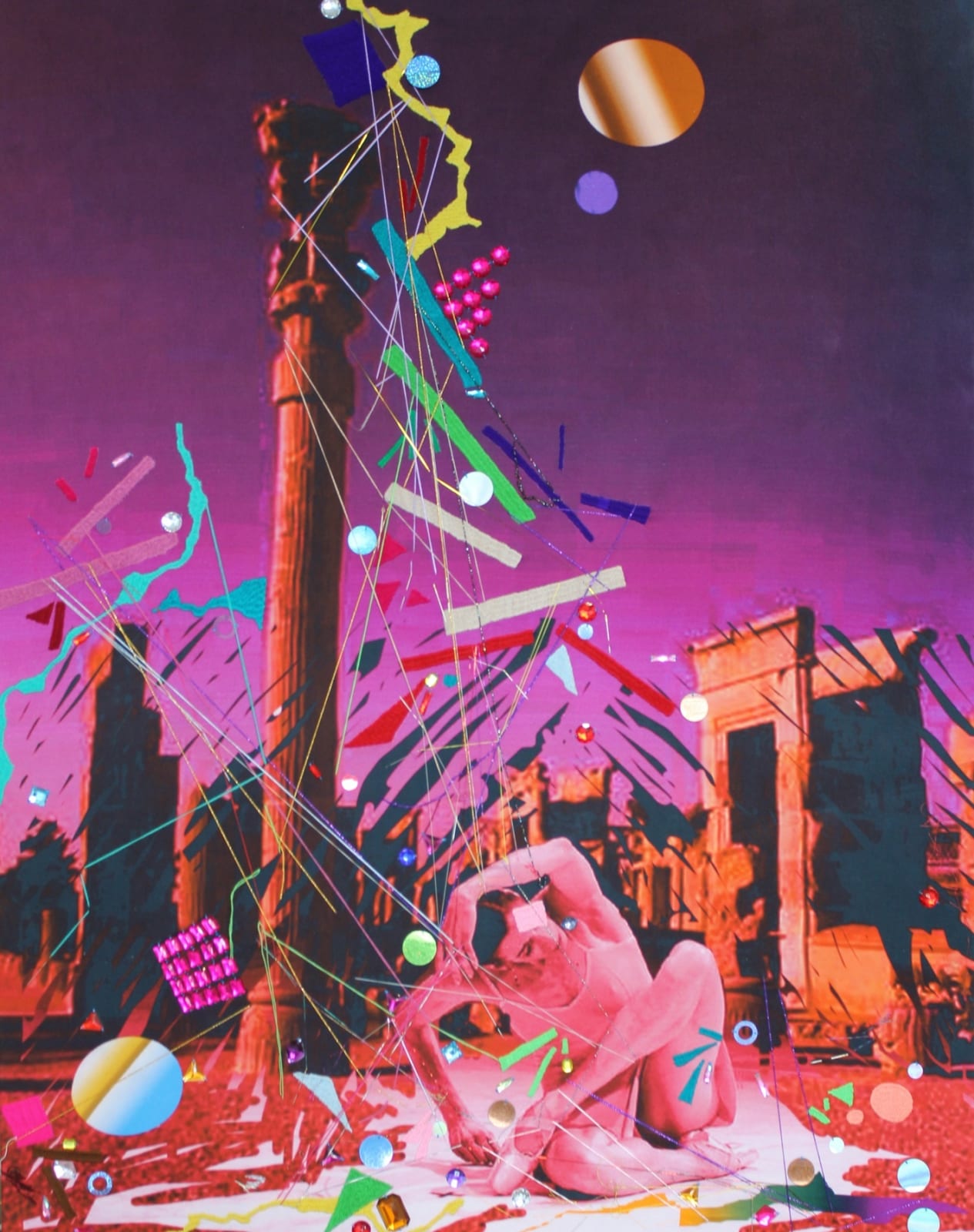

Farhad Ahrarnia b. 1971

Stage on Fire 5, 2012

Hand embroidery on digital photography on canvas

131 x 102.4 cm

52 3/8 x 40 1/2 in

Frame: 148 x 118 x 6.5

52 3/8 x 40 1/2 in

Frame: 148 x 118 x 6.5

Copyright The Artist

In the 20th century, the modernist projects and the rise of nationalism in many countries across the globe anchored and authenticated themselves by reviving and relying on the symbolic language...

In the 20th century, the modernist projects and the rise of nationalism in many countries

across the globe anchored and authenticated themselves by reviving and relying on the

symbolic language of their ancient visual heritage and cultures, in order to lend a greater

weight, and find more effective ways to articulate, brand and seek justification for building

of modern, patriotic and culturally proud nations. National entities which were easily

identifiable and differentiated from one another based on their so called “unique” cultural

traits and customs.

Ironically and paradoxically to be a truly "modern" nation, it also needed to be truly and

authentically ancient, with a history stretching back centuries or millenia.

Images of ancient ruins and architectural sites, old coins and unearthed artifacts, engraving and stone carvings were appropriated and turned into emblems, logos and medals in order to lend a greater significance to these projects of nation building, industrialization and modernisation in general

Iran and many other nations across the Middle East were not exempt from this process. Following a Germanic blue print under the reign of Reza Shah Pahlavi, the process of rebranding Persia, [with a pre-Islamic past] into a modern Iran accelerated. Eventually in keeping and competition with 20th century modernity and contemporaneity, and based on an influx of wealth and expertise, art and music festivals flourished across the region to celebrate and its many histories. A number of these events and performing programs took place on the site of ancient ruins, notably the music festival at Baalbek, and the Shiraz Art festival, partly performed on the site of ʻTakht-e Jamshidʼ, more commonly known as Persepolis.

The excavation of ʻTakht-e Jamshidʼ had begun in the 19th century and was

completed in the early decades of following century. With its cross cultural architectural styles and motifs ʻTakht-e Jamshidʼ came to represent the grandness of a modern Iran rooted in a glorious and expansive past. Yet paradoxically the ruins of this burnt, tarnished and vandalised site also reflect the demise and fall of an empire into foreign hands. Therefore for Iranians ʻTakht-e Jamshidʼ embodies ambivalent feelings and a variety of psychological and politically charged projections and narratives.

For this body of work, Ahrarnia aimed to construct a fantastical visual reference and a space for

dreaming and re-imagining the ruins of ʻTakht-e Jamshidʼ as a modern stage, where the attitudes, techniques and the essence of Moderntiy in various forms of dance were shaped up and performed.

Many famous 20th century composers and modern dance troupes, most notably Maurice Bejart and Merce Cunningham, visited the site and performed on its broken stones, perhaps as a means of awakening the ghosts of its past and becoming entangled with its historical significance and kudos.

Formally the works borrow numerous visual references from the language of constructivist and suprematist paintings in order to suggest movement, tension and entanglement. These visual motifs are embroidered on the surfaces of these works, and are expressed in the language of needlework and ancient vernacular embroidery techniques. The embroidered motifs are modern in their contours and visual suggestiveness, yet completely ancient and “ethnic” in the intensity and heightened textural quality of their formal application and craft engineering. There are also a number of reflective sequins attached to the surface of the works, which with their jewel like appearance animate and refract the light and the overall surface of each work.

across the globe anchored and authenticated themselves by reviving and relying on the

symbolic language of their ancient visual heritage and cultures, in order to lend a greater

weight, and find more effective ways to articulate, brand and seek justification for building

of modern, patriotic and culturally proud nations. National entities which were easily

identifiable and differentiated from one another based on their so called “unique” cultural

traits and customs.

Ironically and paradoxically to be a truly "modern" nation, it also needed to be truly and

authentically ancient, with a history stretching back centuries or millenia.

Images of ancient ruins and architectural sites, old coins and unearthed artifacts, engraving and stone carvings were appropriated and turned into emblems, logos and medals in order to lend a greater significance to these projects of nation building, industrialization and modernisation in general

Iran and many other nations across the Middle East were not exempt from this process. Following a Germanic blue print under the reign of Reza Shah Pahlavi, the process of rebranding Persia, [with a pre-Islamic past] into a modern Iran accelerated. Eventually in keeping and competition with 20th century modernity and contemporaneity, and based on an influx of wealth and expertise, art and music festivals flourished across the region to celebrate and its many histories. A number of these events and performing programs took place on the site of ancient ruins, notably the music festival at Baalbek, and the Shiraz Art festival, partly performed on the site of ʻTakht-e Jamshidʼ, more commonly known as Persepolis.

The excavation of ʻTakht-e Jamshidʼ had begun in the 19th century and was

completed in the early decades of following century. With its cross cultural architectural styles and motifs ʻTakht-e Jamshidʼ came to represent the grandness of a modern Iran rooted in a glorious and expansive past. Yet paradoxically the ruins of this burnt, tarnished and vandalised site also reflect the demise and fall of an empire into foreign hands. Therefore for Iranians ʻTakht-e Jamshidʼ embodies ambivalent feelings and a variety of psychological and politically charged projections and narratives.

For this body of work, Ahrarnia aimed to construct a fantastical visual reference and a space for

dreaming and re-imagining the ruins of ʻTakht-e Jamshidʼ as a modern stage, where the attitudes, techniques and the essence of Moderntiy in various forms of dance were shaped up and performed.

Many famous 20th century composers and modern dance troupes, most notably Maurice Bejart and Merce Cunningham, visited the site and performed on its broken stones, perhaps as a means of awakening the ghosts of its past and becoming entangled with its historical significance and kudos.

Formally the works borrow numerous visual references from the language of constructivist and suprematist paintings in order to suggest movement, tension and entanglement. These visual motifs are embroidered on the surfaces of these works, and are expressed in the language of needlework and ancient vernacular embroidery techniques. The embroidered motifs are modern in their contours and visual suggestiveness, yet completely ancient and “ethnic” in the intensity and heightened textural quality of their formal application and craft engineering. There are also a number of reflective sequins attached to the surface of the works, which with their jewel like appearance animate and refract the light and the overall surface of each work.

Exhibitions

Abu Dhabi Art, Lawrie Shabibi (2015)