-

Mohamed Melehi & The Casablanca Art School

27 MAY 2023 – 14 JANUARY 2024 -

This viewing room provides a unique retrospective insight into the multi-faceted career of Mohamed Melehi (1936-2020, Asilah, Morocco) and explores the influential role of the Casablanca Art School in the development of experimental art practices in Morocco during its most radical period, when Melehi taught there between 1964-1969.

-

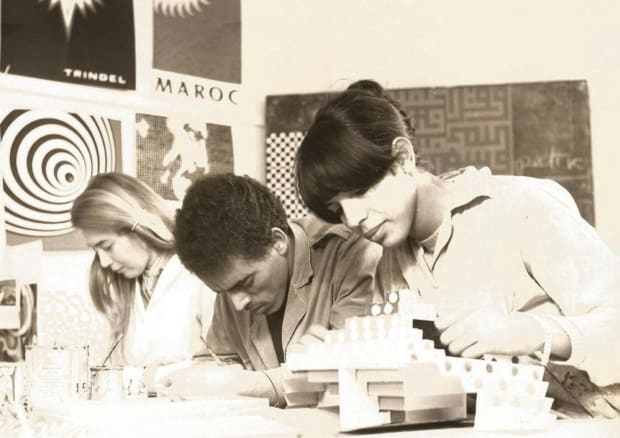

Mohamed Melehi (in chair) at the Casablanca Art School with a group of teachers (including Mohammed Chabâa and Farid Belkahia) and students (among them, on the far right, Malika Agueznay). Photograph by Toni Maraini. Photo: Courtesy of Malika Agueznay

Mohamed Melehi (in chair) at the Casablanca Art School with a group of teachers (including Mohammed Chabâa and Farid Belkahia) and students (among them, on the far right, Malika Agueznay). Photograph by Toni Maraini. Photo: Courtesy of Malika Agueznay -

The Casablanca Art School at Tate St Ives

‘This wasn’t simply an aesthetic revolution, but a pedagogic one,’ says Montazami. ‘Students were encouraged to look beyond Western academic traditions and focus on local ones instead.

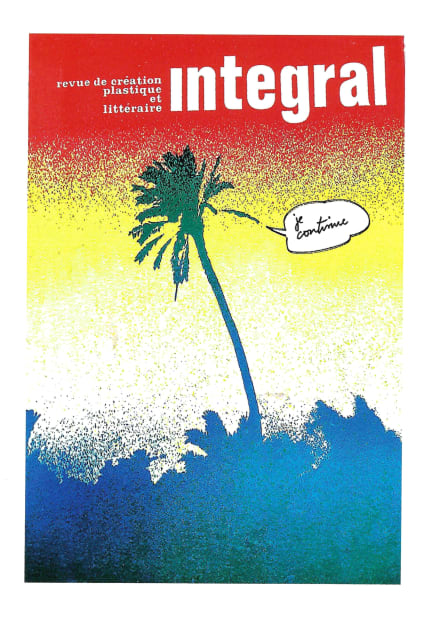

The first ever exhibition in the UK devoted to the Casablanca Art School opens on 27 May 2023 at Tate St Ives. It’s a moment described by its curator, Morad Montazami, as one of ‘rehabilitation’. He means that it shows how avant-garde art wasn’t produced solely in Europe and North America — despite traditional, Western accounts of art history long suggesting that it was.Works by 22 artists will be brought together to demonstrate the wide variety of the Moroccan ‘new wave’, from vibrant abstract paintings and urban murals to applied arts, typography, graphics and interior design. The exhibition will also include a selection of rarely-seen print archives, vintage journals, documentary photographs and films. -

Mohamed Melehi (1936-2020), Untitled, 1983. Cellulosic paint on wood. 150 x 200 cm. © Mohamed Melehi Estate

Mohamed Melehi (1936-2020), Untitled, 1983. Cellulosic paint on wood. 150 x 200 cm. © Mohamed Melehi EstateMohamed Melehi

1936 - 2020Mohamed Melehi was a painter, graphic designer, teacher, muralist, cultural activist and a pivotal and leading figure for postcolonial Moroccan art. Alongside peers Farid Belkahia and Mohammed Chabâa, Melehi was an influential figure in Moroccan modernism and a key member of The Casablanca Art School, an avant-garde group that radically questioned cosmopolitan abstraction and art pedagogy within the context of colonialism. His work resists the East/West divide, resulting in a dialogue between popular and traditional Moroccan craft. Melehi's work is also connected to the hard edge painters of the 1960s.

In Melehi’s art we can sense the spirit of aesthetic revolution and the exaltation of post-Independence Morocco. His creative energy and visual inventiveness are palpable in his works, dating from the 1950s to the 1980s. They trace Melehi’s artistic developments in the 1960s, from experiments with abstraction in Rome and New York to the full realization of his iconic wave motif in the 1970s. Additionally, Melehi's significance in transnational art history becomes evident in this period. Melehi’s work resists the East/West divide that developed during the Cold War period. His wavy Third World frescoes take us on a cosmopolitan journey, joining together the Mediterranean and the Atlantic.

-

M. Melehi, mural painting, Nouasser airport, Casablanca, 1973

M. Melehi, mural painting, Nouasser airport, Casablanca, 1973 -

Casablanca’s Ecole des Beaux-arts

-

-

Mohamed Melehi (left) at his studio in Casablanca with Mohammed Chabâa. Photo: © M. Melehi archives/estate

Mohamed Melehi (left) at his studio in Casablanca with Mohammed Chabâa. Photo: © M. Melehi archives/estate -

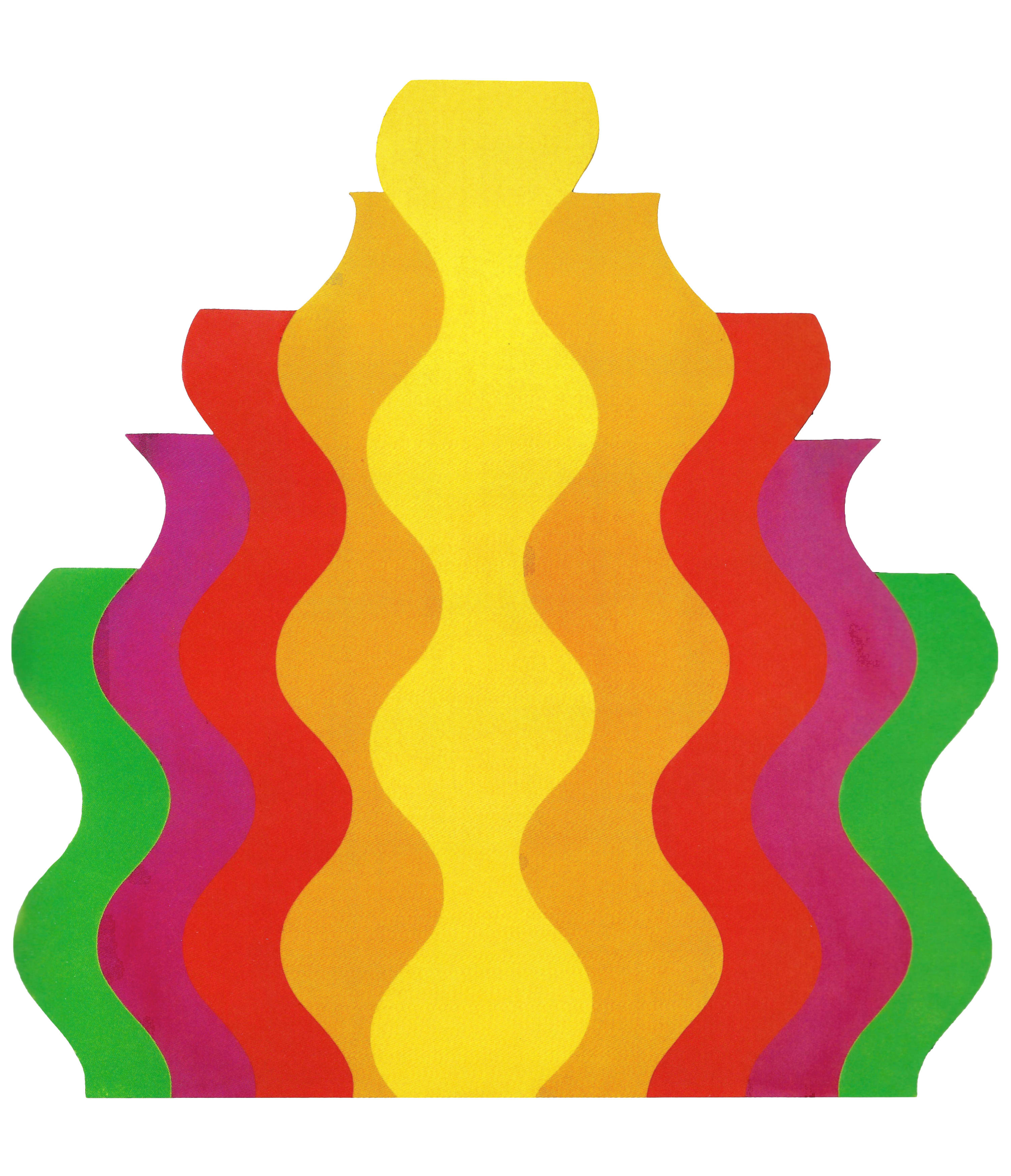

Mohamed Melehi, Flame, 1976, Cellulose paint on cut-out panel, private collection.

Mohamed Melehi, Flame, 1976, Cellulose paint on cut-out panel, private collection.Mohamed Melehi made a significant change to his artistic approach in 1969 and 1970. He abandoned the use of canvas and traditional oil or acrylic paint in favor of wooden panels and cellulose paint, resulting in a more impersonal and neutral aesthetic. This shift towards using industrial materials and techniques aligned with the Russian Constructivists' belief that art should be a means of production rather than a means of individual expression. Melehi's adoption of these methods meant that he utilized tools and accessories traditionally associated with workers and industry rather than those of a painter. He even delegated the production of his works, which was consistent with a history that began with Moholy-Nagy's order for paintings executed in porcelain-enamel from a sign company in 1922.

Initially being produced in a workshop, the cellulose works were then created in the artist's studio, which was adequately equipped for the task. Despite this industrial production process, Melehi's works remained true to their origins. The humble motifs he borrowed were entirely removed from the grand ambitions of traditional art and were faithful to their artisanal origins.

-

-

-

Mohamed Melehi at his L’Atelier Gallery solo exhibition in Rabat where his silkscreens were exhibited, 1971.

Mohamed Melehi at his L’Atelier Gallery solo exhibition in Rabat where his silkscreens were exhibited, 1971.Melehi was one of the first artists to exhibit in one of the first Moroccan independent art spaces, L’Atelier in Rabat, founded by Pauline de Mazières. The exhibition featured the slikscreen Flame, 1970 among others and Melehi would continue to contribute as a designer to the gallery’s visual style and communication.

Between 1985-1992 he took up on a new position at the Ministry of Culture, contributing to the development of art spaces and cultural institutions in Morocco and leading major restoration projects, including the Tinmel mosque in the High Atlas. Between 1999 and 2002, he worked as a cultural consultant to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The exhibition follows three principle chapters. It highlights Melehi’s urban wanderings between the cities of Rome, New York and Casablanca, the stimulation of new visions, and the dream of sharing them with a community that would transcend school, art factory, or design studio… and, finally, the nomadic museum or migratory forms.

-

'Melehi’s recent works revive the paradox of the wave, that which is both organic and ornamental, but also ultimately has no beginning and no end. They reinforce Melehi’s contribution to the rethinking of decorative function and grammar of art, and echoes his lifetime commitment to mural painting and urban design. Melehi’s waves resonate both in the past and the present, as a visual metaphor for breaking the rules, expanding our vision, and broadening our minds.'

- Morad Montazami, Curator of Casablanca Art School exhibition at Tate St Ives

His most recent Moucharabieh (2020) series is reminiscent of his bold graphic compositions from the early 1970's, where he produced the now-familiar wave motif in block colours, yet now on a much grander scale. The motif of the wave is, for Melehi, all about movement and change. It is as much about electromagnetic radiation as it is about water, and when vertical it becomes a flame. The series strips away the waves to their bare essentials – they become all-over diagonal compositions - giving emphasis to the curved line, hyper-graphism and a clear chromatic palette.